RECORDING REVIEWS/

COMPTES RENDUS D’ENREGISTREMENTS

Hearing Place in “Location Recordings”

The Bristol Sessions: The Big Band of Country Music (BCD 16094). 2011. Five compact discs and accompanying book by Tony Russell and Ted Olson. Bear Family Records, Holste-Oldendorf. 120 pp.

The Johnson City Sessions: Can You Sing Or Play Old Time Music? (BCD 16083). 2013. Four compact discs and accompanying book by Tony Russell and Ted Olson. Bear Family Records, Holste- Oldendorf. 136 pp.

LEE BIDGOOD

East Tennessee State University

This essay considers the Bristol, TN/VA (1927-1928) and Johnson City, TN (1928- 1929) Sessions recordings released by the Bear Family label, as well as recordings, made by linguist Joseph Hall in the 1930s, of musical performances by residents of the Smokies in eastern Tennessee and west- ern North Carolina. I also consider here a collection of performances, by contempor- ary artists, of songs that Hall recorded in the 1930s. This essay is informed by my experience as a musician who has listened to, played, and written about the string- based vernacular music often called “old time music.” Like others who style them- selves connoisseurs of this music, I have paid careful attention to the content and context of recordings like those I consider here. I am particularly interested in these recordings since they are part of my current local environment; I currently live near the sites of these recordings, my work as a per- former and teacher involves using these recordings, and I work with people who were involved in the production of these collections. I chose these four collections because I am curious about what sense of place they afford other aficionados of old time music. My experiences with these recordings lead me to consider the larger question of how contemporary audiences and producers of old time music consume, engage, and create a sense of place through their music-making (listening, performing, mediating, etc.). As a participant-observer in old-time music-making circles, I have observed that we seem very concerned with place.

In addition to collections of recordings that are grouped by performers, there are many collections valued by music-makers in old time revivalist circles that bear geo- graphic labels such as “Traditional Fiddle Music of Missouri,” “Kentucky Mountain Music,” etc. What role do these place iden- tifications play? How does a title like “The Bristol Sessions” signal a geographic terri- tory, and how might it establish a sense of

Recording Reviews / Comptes rendus d’enregistrements 277

This review has an accompanying video on our YouTube channel. You can find it on the playlist for MUSICultures volume 45, available here: http://bit.ly/MUSICultures-45. With the ephemerality of web-based media in mind, we warn you that our online content may not always be accessible, and we apologize for any inconvenience.

278 MUSICultures 45/1-2

difference from other places and perform- ances? How do we use elements drawn from these recordings to conjure a sense of place through our own musical efforts?

The Bear Family compilations of recordings made in Bristol, TN/VA and Johnson City, TN are significant research and production efforts made by a team intent on including all relevant facts and media (including advertisements, news- paper articles, photographs, etc.). The Bristol Sessions set compiles 124 record- ings made in 1927 and 1928 by the Victor Talking Machine Company onto five CDs; The Johnson City collection includes four CDs with 100 separate recordings made in 1928 and 1929 by representatives of the Columbia Phonograph Company. Included as part of each box set is a book (“liner notes” is a significant understate- ment, each book is hardcover and more than 100 pages in length) in which Dr. Ted Olson (professor at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, TN) and veteran discographer Tony Russell provide interpretive text to accompany the record- ings.

The producers’ notes balance cele- bratory and critical tones in discussing the people, sounds, styles, locations, and recording processes involved. They provide careful readers with a complicated set of place-signifiers as we read, listen, and form a sense of “genius loci” for these sounds and the people who made them. Place of birth is a common way to create a context for an old time performer, for example as a “Kentucky fiddler” or a “Piedmont North Carolina blues guitarist.” The musicians recorded in our current slate of four col- lections were not always from the place where they were recorded. For example, Russell and Olson explain that many of

the performers who made recordings in Johnson City in 1928 and 1929 travelled extensively to do so, giving the example of a cadre of performers who travelled from the Corbin, KY area.

A further challenge to a simplis- tic or monolithic “hearing” of place in these sets is the wide range of geographic places about which the performers sing. The verses of Clarence Green’s “Johnson City Blues” take listeners to Chattanooga, Memphis, and back to Johnson City, using a well-worn place-based narrative model used by many performers in the 1920s and 1930s, including the Allen Brothers in their lyrically similar “Chattanooga Blues.” The Bowman Sisters, although they were one of the local groups from the Johnson City area, performed material that ranged far afield, including Stephen Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home” and “Swanee River.” They were clearly aiming to participate in a music industry that was paying attention to the wide range of rural imaginaries that were a part of the growing “hillbilly music” industry of the late 1920s.

Clarence “Tom” Ashley’s recordings made in Johnson City in 1929 provide a more concentrated sense of place through limitations. His distinctively rural and non- cosmopolitan vocality, focused banjo style, and mode of storytelling might have been absorbed through his childhood in Bristol, TN and his youth outside Mountain City, TN. On the other hand, they also might have been something that Ashley picked up from traveling minstrel or medicine show troupes.

In any case, Ashley’s recordings evoke a sense of rural, pre-modern existence, sketch- ing a drama of simplicity with extremes of bliss and tragedy juxtaposed. In an interest- ing twist, Ashley’s “Coo Coo Bird” is one of

the recordings in this set that has had the most active circulation. This is especially due to its inclusion in Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, a compilation (organ- ized by theme and function, not location of recording) released by Folkways Records in 1952 which was a key inspiration and source of material for folk revival figures, including Bob Dylan. Olson and Russell inform us that Ashley’s musical work put him, not in idyllic wilderness locales, but at the heart of the full-throttle industrializa- tion of the Tri-Cities region around Johnson City, surrounded by factories, mines, and the ubiquitous call of passing trains. In Ashley’s recordings, we hear an absence of the modernization in which he lived, and to which his sounds were a balm, if not an antidote. When old time music fans today listen to his records without this context, we don’t hear this part of Ashley’s actual place and time — the modern element that (per T. J. Jackson Lears) is often entwined with the anti-modern.

One further note about technol- ogy: the sound quality of the Bear Family releases is exceptional. Much care seems to have been taken to preserve extant sounds and to provide the cleanest and most listen- able example of what was performed into the microphones used by Victor and Col- umbia in the late 1920s. The recordings — as they are processed for this collection — are in better shape than many historic recordings due to sophisticated, tasteful clean-up processing that has made them sound more like part of the sonic universe of the 21st century.

Consider another way to experience the sounds on these Bear Family collec- tions: navigate to the YouTube channel of a record collector like “Columbia1930” who has posted a high-quality video of the playing of the record “Lindy” (Columbia 15533-D) by the Proximity String Quar- tet (made in Johnson City in 1928), in which you hear not the traces of a modern mastering studio, but the sound of this rec- ord collector’s listening room.1 While this video posting includes the “room noise” of this unprocessed modern video recording, it also includes the sounds and motions of the phonograph’s stylus coasting through the grooves as the spinning slows. These are the sounds that ignited this person’s passion for and connoisseurship of these records. Unlike the conventions of “box set” collections, a different balance of technology, marketing, and experience is audible (and visible). In the past, Bear Family sets might have provided the only access audiences would have had to rare historical recordings; now, a huge num- ber of such recordings are available on YouTube and other social media sites. On these newer, networked media spaces, the recordings seem to have a different role, one bound less to commercial consump- tion and more to individual engagement with these recordings.

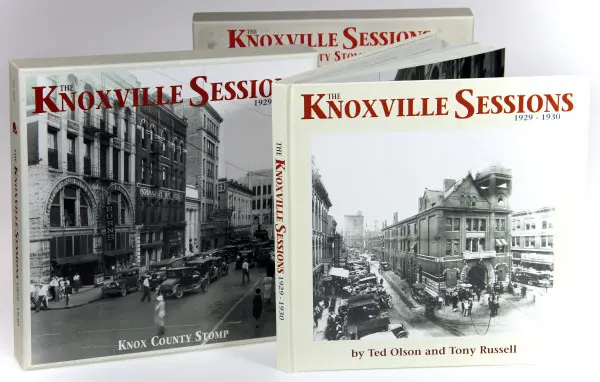

Bear Family is not the only institu- tion constructing larger narratives that purposefully connect sets of recordings to locations where they were made. The Bear Family’s Bristol set, in codifying location and sound, has supported a number of initiatives, such as a Bristol museum that names the city as the “Birthplace of Coun- try Music” and is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the 1927 recording sessions.2 In addition, a separate Bear Family release of recordings made in Knoxville, Tennes- see provided leverage for the “Knoxville Stomp: Festival of Lost Music” in 2016.3

While Russell, Olson, and the Bear Family production team have tried to

Recording Reviews / Comptes rendus d’enregistrements 279

preserve, illustrate, and (perhaps) elevate these sounds, they have also made them into something different. Instead of dis- crete discs, or even record sides, they are now tracks that are part of a larger pro- ject and the “Sessions” become framed as the work of a single producer. Columbia A&R representative Frank Walker is listed as “producer” of the Johnson City set — a somewhat symbolic move by the Bear Family producers. This attribution makes some sense, as Walker ran the sessions. However, this homage seems misplaced, since Walker is not responsible for the re- presentation of these recordings as a set — he sought to produce individual records. In the Bristol set’s liner notes, Olson and Russell state clearly that RCA Victor rep Ralph Peer’s vision was not one of docu- mentation. In recruiting artists to record for Victor in 1927 and 1928, he was try- ing to cut profitable records, not represent Bristol through these recordings. Label- ing the recordings “The Bristol Sessions,” however, creates a marquee place-label that overshadows Olson and Russell’s careful work to describe the individual origins of artists. While a single place designation for these sets is much easier to understand (and is perhaps more marketable), this kind of simplification doesn’t tell the whole story.