Arkansas Democrat-Gazette/KIRK MONTGOMERY

Let the story begin in "a canvas-covered cabin in a crowded labor camp."

That's where Merle Haggard kicked off his greatest song, "Hungry Eyes," which he recorded with his band The Strangers, augmented by James Burton, in December 1968 and released in February 1969 in advance of his greatest album, A Portrait of Merle Haggard.

Daily Email Newsletters

Stay connected and informed with ArkansasOnline.com news updates delivered straight to your inbox.

The track was recorded in Hollywood's landmark Capitol Records Tower, the 13-floor circular building that is said to resemble a stack of records on a turntable with a spindle extending skyward, at 1750 N. Vine St., just north of the intersection of Hollywood and Vine, and 105 miles south southeast of a scrubby city on the Kern River near the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley called Bakersfield.

Maybe Los Angelenos think of Bakersfield as redneck country, an oil and agriculture podunk place, but from the 1940s through the mid-1970s it was at least country music's second city, if not its alternate capital.

The Bakersfield Sound is an identifiable strain of the genre that combines traditional country elements such as stinging steel guitars and snarling Telecasters with an attitude informed by the perspectives of outsiders, the Dust Bowl refugees that poured into California from Texas, Arkansas and Oklahoma by the hundreds of thousands: hillbillies, Arkies, tin-can tourists, harvest gypsies, fruit tramps and Okies.

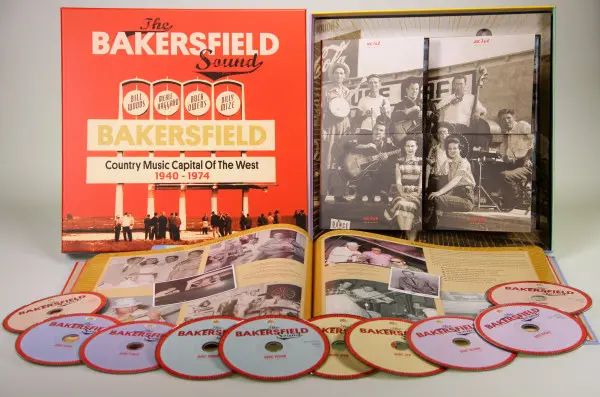

No version of "Hungry Eyes" appears on The Bakersfield Sound: Country Music Capital of the West, 1940-1974, a 10-CD 299-track seven-and-a-half-pound boxed set produced by Germany-based Bear Family Productions ($190.91 at bear-family.com), probably because it would have been too expensive to obtain the rights. But it does come with a handsome coffee table book researched and written by Los Angeles musicologist Scott Bomar, who might rightfully be designated the author of this collection.

"I'll go out on a limb and assume that, if you've invested in a 10-disc boxed set that anthologizes Bakersfield's rich country music tradition, you're already a fan of Buck Owens and Merle Haggard," Bomar writes in his introduction to the set's companion book. If you already have access to "Hungry Eyes," you already know that though Haggard wrote the song as a tribute to his mother, it is not strictly autobiographical.

Haggard never lived in a "canvas-covered cabin"; he grew up in a repurposed boxcar, and his aunt and uncle did live in a labor camp tent where, after his father died, 12-year-old Merle spent a lot of time. His mother worked long hours as a bookkeeper as Haggard famously got into trouble. He went to prison and got into more trouble. In 1960, he spent a week in solitary confinement for making beer, where he watched Caryl Chessman, the kidnapper, rapist and author, prepare for his long-deferred execution.

This experience contributed to scaring Haggard straight, and while it is often said that Haggard's "Sing Me Back Home" was inspired by the execution of Haggard's friend James "Rabbit" Kendrick, with whom Haggard once plotted an escape from San Quentin, Haggard had been sprung from the joint by the time Rabbit walked his last mile. But he was there for Chessman's, and he remembered the eerie feeling that fell over the prison, the singing of hymns and the quietus.

But if you want "Sing Me Back Home" or more Haggard biography, that's easy enough to get. The Bakersfield Sound has plenty of Merle, and a lot of Buck, but it's more about what you don't know and might never have expected. Haggard once said that he and Owens were simply the end product of what had been fomenting in and around Bakersfield since before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

The first six tracks of the set are field recordings of migrants who'd come to pick peas and almonds; the most professional of these is "Get Along Down to Town," by the King Family, a string band consisting of Henry King and his two sons and daughter that entertained at Saturday night dances held at the migrant farm labor camps.

Even before they were recorded by Library of Congress fieldworkers Charles L. Todd and Robert Sonkin in 1941, they had performed in the barn dance scene in John Ford's 1940 film The Grapes of Wrath. (Todd and Sonkin's field recordings of the King Family can be found at loc.gov/audio/?q=king+family.)

From there the set proceeds in roughly chronological order, offering tracks from forgotten artists and superstars alike that make a substantial case for the importance of Bakersfield as a pop music pole.

Bomar makes a lot of interesting choices -- while Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys mightn't be associated with Bakersfield in the popular imagination, they did have an indelible influence on the musicians who are associated with the city.

In the mid-'40s Wills' operation was California-based and regularly played the Beardsley Ballroom. Their particular mixture of blues, jazz, swing and proto-rockabilly -- as suggested in their 1945 cut "Seven Come Eleven" featured on CD1 of The Bakersfield Sound -- prefigured the approaches used by Buck and Merle, the mega-successful end products of the Bakersfield foment.

"Okie Boogie," a 1948 track by The Maddox Brothers and Rose, marries a whining steel guitar to a pounding rhythm, suggesting that rock 'n' roll was already in the air. Leon Payne's version of "Lost Highway" -- the better-known version is Hank Williams' cover -- was recorded in Dallas, but immediately after Payne's sojourn in California. (As Bomar points out, his talking on the track as band members solo is right out of the Bob Wills playbook.)

A second Maddox Brothers and Rose track on the first CD, "Water Baby Blues," marks the first appearance of the remarkable guitarist Roy Nichols, who would go on to be a mainstay of Haggard's Strangers and handle the electric guitar parts (with Burton stabbing acoustic chords) on "Hungry Eyes."

Nichols would also figure prominently on recordings by Lefty Frizzell, Johnny Cash and Wynn Stewart. (Although he never lived in the city, Stewart is one of the most important figures in the story of the Bakersfield Sound; he served as mentor and inspiration to Haggard and Owens, both of whom incorporated elements of his idiosyncratic vocal phrasing into their own very different styles. Eventually, Owens -- who ended up being as much as an impresario and businessman as artist -- became Stewart's patron and champion.)

Wanda Jackson also shows up on the set, though her chief contribution to Bakersfield's legacy involves her introducing her boyfriend Leonard Sipes, who would become a member of the Rockabilly Hall of Fame as Tommy Collins, to the scene when he tagged along on a trip her family took to California in 1952.

Sipes hit it off with Ferlin Husky, who got him signed at Capitol Records, where he gave Buck Owens his first real recording gig as a studio guitarist and where he talked to Merle Haggard about how great songs are made, which caused Haggard to start to really think about his lyrics, which led to the plainspoken poetry of tracks like "Hungry Eyes." (Haggard's 1981 hit "Leonard" is about Collins.)

Yet as authoritative and catholic as this set is -- you can hear all the strains of American pop, folk, jazz, gospel and Latin strands braiding together on the first couple of discs -- it still feels as though we're just scratching the surface. Collins, Buck Owens' longtime musical collaborators Don Rich and Fuzzy Owen -- who quit Little Rock for Bakersfield in the late 1940s -- are just three of the figures who pop up here and there in the set but deserve long excavations of their own. Bomar can't get around to everybody, the map can't be as big as the territory, and sometimes you just have to dig things out on your own.

Sometimes that ain't easy. I'd really like to know more about "Pusan," a jumpy novelty blues about the Korean War (alluding to the "burp gun boogie," a reference to the Soviet PPSh-41 sub-machine gun) that Billy Mize cut with Bill Woods & His Orange Blossom Playboys, who included, Bomar tells us, Owen and his cousin Lewis Talley, with Mize playing steel guitar and Woods, a Texan who arrived in Bakersfield in 1946, on vocals and piano.

Bomar credits Woods with boosting the careers of Haggard and Owens -- who was the Playboys' lead guitarist and sometimes vocalist from 1951-58 -- but there's virtually no specific information about this available on the internet other than a YouTube video that displays the record label, revealing the songwriter as Fuzzy Owen and the misspelling "Palyboys."

Mize went on to a healthy career in regional television and wrote songs for the likes of Barbara Mandrell, Glen Campbell and Bobbie Gentry, and scores 10 tracks on this anthology.

But "Pusan" feels like something that's slipped in from an alternate timeline, from some parallel universe.

MIGRANT CAMPS AND HONKY-TONKS

One overly simplistic way of talking about the Bakersfield Sound is to cast it as a reaction to Nashville.

Nashville is Carter Family, gospel-derived, humble sinners who understand how negligible they are in the cosmic sense. Leaving aside that, in the beginning, Nashville was reluctant to embrace "hillbilly" music, we can say Nashville country music comes out of the churches.

Bakersfield country comes out of someplace rougher, out of the migrant camps, out of the honky-tonks. Whether it was true or not, Buck Owens always said that his family was a week away from starving in Texas when they tried to come to California.

Tried, because they were met at the border that first time by police officers who wouldn't let them in because they lacked, in Woody Guthrie's parlance, the "do-re-mi." The Owenses eventually made it to California, and Buck eventually became one of the most powerful and richest men in show business, but he never lost that chip.

While what developed in Bakersfield in the '60s was more anchored in tradition than the countrypolitan sounds that Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley were producing in Nashville, you can't argue that Bakersfield was any less professional.

You might get that impression listening to this set because Bomar has rightly included a lot of artists who'll be unfamiliar to even the most devoted fans of the genre -- his note on track 17, disc eight, a song called "Night Life Is My Weakness" by Dave Price, tells us the band comprises "likely not top tier pickers, as the fiddle work is sloppy and slightly off-key." Bomar isn't about presenting us with a Best of Bakersfield -- for that, you'd have to dive deep into Owens and Haggard's familiar catalogs. That's a job for Spotify.

No, this work is deeper, more academic and not for everyone. (There's a reason Bear Family is mainly a mail-order operation; one could imagine this set sitting on a record store shelf for a long time.)

A DEEP DIVE

Yet this is a fascinating and rewarding dive into the roots of the Bakersfield phenomenon. Bomar is doing archaeology rather than imagining the cosmic quantum. There's an awful lot of great music among the more than 12 hours he has collected, a lot of great songs, a lot of great playing, plenty of Merle and Buck and Joe Maphis and Ferlin Huskey and Jean Shepard. But the meat of the set is the unreleased and barely released studio recordings, demos and radio performances by names familiar, obscure, and, in one track, only guessed at.

It winds up in 1974, the last year Haggard lived in Bakersfield, when Buck Owens' string of Top 10 hits finally came to an end and when, tragically, Owens' longtime guitarist and harmony singer Rich died in a motorcycle wreck. Which is as good a place as any to end it. Buck and Merle are gone now, if you Google "Bakersfield, Ca." you'll scroll through pages before finding anything directly music-related.

A companion project might take the shape of something akin to Dwight Yoakam's "Greater Bakersfield" thought experiment, which he pursues on his satellite radio station and channel. Because Bakersfield is really West Coast country music -- that Capitol Records Tower where "Hungry Eyes" was recorded was also a flag thrust in the soil by EMI after it acquired Capitol Records in the '50s.

It was the first major record label outpost on America's West Coast. Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, the Wrecking Crew, the Beach Boys, the Monkees all made records there.

Clarence White -- who appears on this set -- links the Byrds to Bakersfield. "Faraway Eyes" links the Rolling Stones. The studio musicians who made up the Fraternity of Man were obviously imitating Buck Owens and Don Rich on their only near-hit, "Don't Bogart Me" (which was featured on the soundtrack of the film Easy Rider). Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead were huge fans of Owens and Haggard; Weir has said they modeled the band after Owens' Buckaroos. The Beatles covered "Act Naturally."

You could argue that Bakersfield conquered the world.