Who was/is Lester Flatt & Bill Monroe ? - CDs, Vinyl LPs, DVD and more

Lester Flatt & Bill Monroe

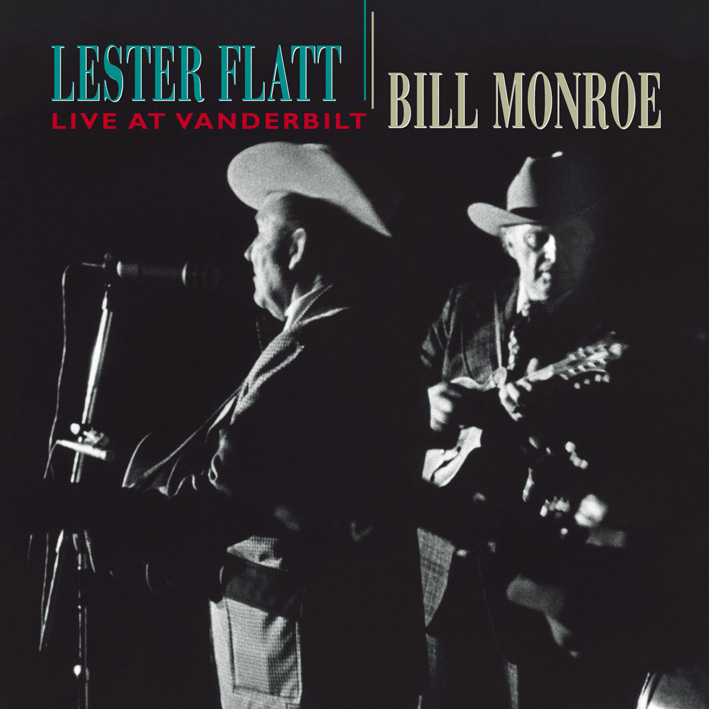

Live at Vanderbilt

From Thomas Goldsmith's notes to 'Flatt On Victor… Plus More.'

From Thomas Goldsmith's notes to 'Flatt On Victor… Plus More.'

A famous bluegrass reconciliation had taken place in 1971. Lester Flatt and Bill Monroe hadn't spoken since 1953, when Monroe got irked over the arrival of Flatt and Scruggs at WSM; in fact, Flatt had vowed that if anyone spoke first, it would be Monroe. This, Flatt's manager Lance LeRoy told me in 1999, is the way they got back together: Monroe decided he wanted Flatt to play Monroe's Bean Blossom Bluegrass Festival up in Indiana and deputized his son James to act as emissary. "James came over to me one night at the Opry," LeRoy said. "He said, 'Daddy's interested in having Lester play Bean Blossom.' I said, 'Give me a half hour and I'll see what he says.'" All this was taking place backstage at the old Ryman Auditorium, where the Opry was still holding forth — and where Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs had avoided each other for year after year. LeRoy told Flatt what Monroe wanted. "Lester said, 'Ahh, if he pays the price and I don't have to speak to Bill, as long as we can do our show and get our money and get out, I'll do it.'" James Monroe agreed to those terms and duly sent LeRoy a contract.

Flatt came to the festival fully expecting to play his shows and leave, but as he was in the backstage area preparing to go on, it happened. "Lester was looking out the window and felt a tap on the shoulder and Bill was standing there with his hand out saying, 'Welcome to Bean Blossom,'" LeRoy said. Within minutes, the two former partners were talking as though the 18-year gap had never happened. The reconciliation led to several appearances in which Monroe and Flatt sang together, including the notable Vanderbilt University show.

The Vanderbilt recording of March 19, 1974 shows Flatt in his element: presiding over his band with confidence and ease, and wielding his storied country charm for a rapt student audience. "I think we both felt the same way as far as how to run a show; we wanted a family-type show," Scruggs recalled, adding that he and Flatt saw the value of varying a show with instrumentals and other features: "We were tying to extend our lives as performers." The band at the college concerts included Curly Seckler, one of Flatt's earliest colleagues, adding a deep-country touch with his edgy tenor voice and infectious on-stage personality. On the other end of the age continuum was Marty Stuart, though he was already showing maturity as a musician at age 15. He shines throughout, though his mandolin is sometimes low in the mix. Stuart was already thinking and listening all the time; check out the little harmony he plays under the ending to Flint Hill Special.

Whether influenced by the setting or some other factor, Flatt eschewed the Music Row songs and other more recent material for a night composed almost entirely of bluegrass favorites and some public domain material. The Flatt and Scruggs songbook got a major workout with songs including Flint Hill Special, Lost All My Money (the song usually known as Long Journey Home), Homestead On The Farm, Dig A Hole In The Meadow, Get In Line Brother, Salty Dog Blues, Martha White Theme, and, of course, Foggy Mountain Breakdown.

The recordings also serve as a reminder of Flatt's legendary skills as a relaxed master of ceremonies. "I think he felt very capable, very experienced," former sideman Vic Jordan said of his days with Flatt. "He was a good leader and a had good band to work with. I think he was just comfortable with it, he had done it so long, first with Bill Monroe and then with Flatt and Scruggs. When you've been through the kind of popularity that both those bands had gone through, nothing really worried him."

Recording took place in the basement of Vanderbilt's Neely Auditorium, where RCA had brought mobile equipment. LeRoy remembers sitting in the basement room with engineer Chuck Seitz to help Seitz understand what the band was doing. "I had seen the show so much," LeRoy recalled. "I was so familiar with who was going to take the next break that I could say, 'Paul Warren's going to take the next fiddle break.' It wound up the album was virtually mixed when they were through with it."

Producer Bob Ferguson's recollection is also that the concert taping was low-keyed. "We were in a little room that they had set aside there. I would go back and forth from the hall to the room. Recording with those guys, it was more like the Opry — they pitched and we caught." It might seem that Flatt would take a slightly more formal approach to a performance recorded for an album. But true to form, he was his customary off-the-cuff self, calling out song selections on the spot at several points during the show. He called for several Opry-style encores: repeating the last chorus or so after songs that were especially well received. And there's the entertaining notion of Lester Flatt, an East Tennessean with a distinctive accent, offering an impression of Roy Acuff, another East Tennessean with a distinctive accent, on Wabash Cannonball. Some of the tunes feel rushed, perhaps by the excitement of the occasion. But Flatt usually had the last say in such matters.

Lester Flatt & Bill Monroe Live At Vanderbilt

Read more at: https://www.bear-family.com/flatt-lester-und-bill-monroe-live-at-vanderbilt.html

Copyright © Bear Family Records

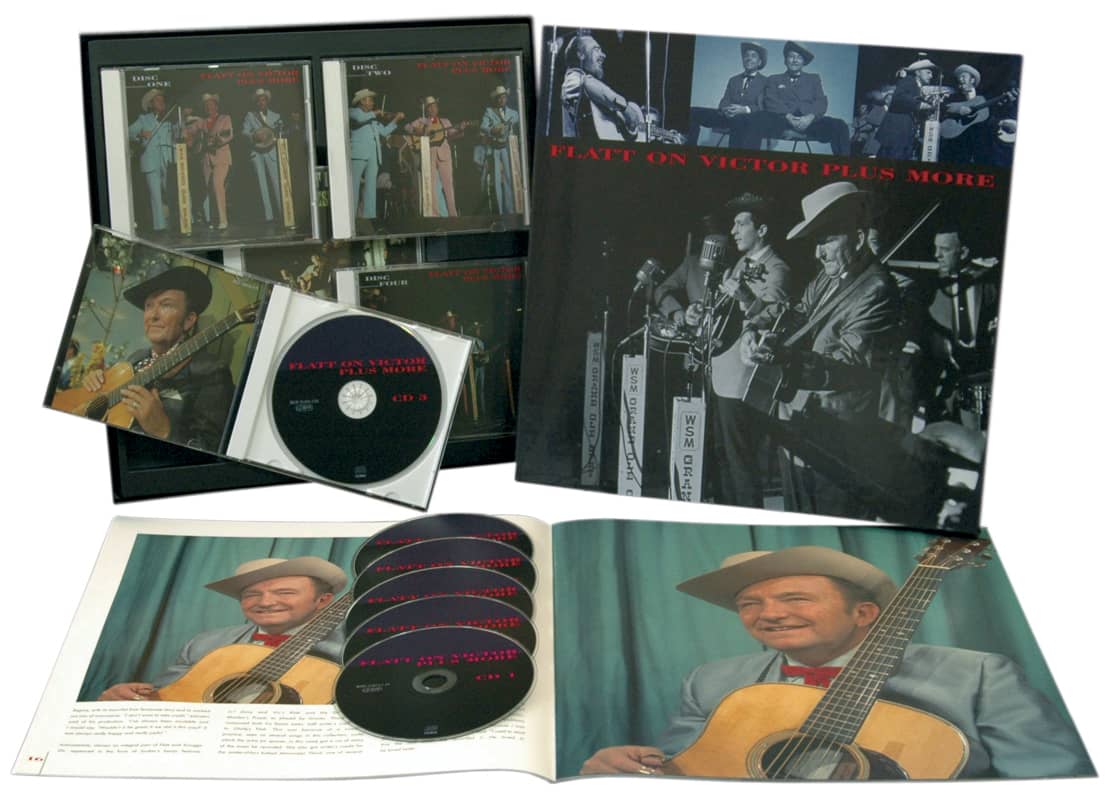

LESTER FLATT

FLATT ON VICTOR, PLUS ...

It was the late '60s and Lester Flatt, like many Americans, had come to a crossroad. His more than 20-year partnership with Earl Scruggs had been crumbling for many months. It was clear that they had drifted apart, musically and personally. Flatt had earned stardom as a great vocalist, unmatched stage personality and bluegrass-country loyalist. He was at odds with Scruggs, the banjo master who had leap-frogged the competition to bring the old minstrel-show instrument into post-war prominence. Their musical and personal division had deeper roots, it seems now. That is, their differences reflected the country's Vietnam-era generational split. Both men came from the country, but Scruggs, who had teen-age sons, was leaning toward the music and style of sixties counterculture. Meanwhile, Flatt, at 55 almost 10 years older, clung to the traditional sounds and country ways that had worked well for the duo for so long.

It was the late '60s and Lester Flatt, like many Americans, had come to a crossroad. His more than 20-year partnership with Earl Scruggs had been crumbling for many months. It was clear that they had drifted apart, musically and personally. Flatt had earned stardom as a great vocalist, unmatched stage personality and bluegrass-country loyalist. He was at odds with Scruggs, the banjo master who had leap-frogged the competition to bring the old minstrel-show instrument into post-war prominence. Their musical and personal division had deeper roots, it seems now. That is, their differences reflected the country's Vietnam-era generational split. Both men came from the country, but Scruggs, who had teen-age sons, was leaning toward the music and style of sixties counterculture. Meanwhile, Flatt, at 55 almost 10 years older, clung to the traditional sounds and country ways that had worked well for the duo for so long.

The upheaval and the split that finally occurred in February 1969 carried huge significance for music fans. The very names Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs embodied authentic country twang and had for a generation. And their image was among the most familiar of any tradition-based act in American music history: when the Country Music Foundation issued the landmark 1985 volume 'Country: The Music And The Musicians,' the cover shot of Lester and Earl and their Foggy Mountain Boys band served as shorthand for the music's long history. In retrospect, theirs was an unusual duo. It's rare that a lead singer and a lead instrumentalist, instead of two singers, make up a popular act. But their years of success paid clear tribute to the specific alchemy formed by Scruggs' instrumental prowess and Flatt's warm vocal presence, songwriting and MC work. Thirty years later, friends and associates of Flatt remember that his down-home ways of singing and entertaining never slipped because they so purely represented the man himself. "It's trite to put it this way, but they broke the mold when they made Lester," his old friend Mac Wiseman told me in 1999. "He was a mountain man and he had mountain ways." Flatt's singing echoed his country background. His voice, deeper than most bluegrass singers', conveyed the heart of songs with a gently insinuating quality, carried by little gliding runs and downward turns. A slight sibilance and his habit of sometimes sliding up to pitch just added to the distinctiveness of his style. Flatt also used the ghost of a yodel at the ends of phrases and a deeply country way of saying his words. "He had the best phrasing," said Bob Johnston, who produced Flatt and Scruggs' last sessions as well as a Flatt solo LP. "And he never thought about it. He would hold that guitar up and he had a big smile on his face and he had the love of the life." Flatt's steady rhythm guitar playing featured one of the few country instrumental licks named after one person, the 'Lester Flatt G-run.' The quick, thumb-driven bass figure he developed to keep up with Bill Monroe's flying mandolin became one of the signature sounds of bluegrass. And his strong, heart-direct songs fill many pages in the bluegrass-standard songbook. But it is on Flatt's personality that his legend may rest most firmly. "In addition to his singing, one of his greatest attributes was his MC work," Wiseman said. "He didn't talk down to people and he didn't talk up to people; he was just himself. He didn't have to work at it." Recalled Vic Jordan, who took over banjo duties with Flatt after the breakup: "When he talked and when he sang and the way he acted, that's who he was."

So it was that in the '60s, when everything was changing, Flatt did not. To judge by photographs and recordings through the years, Flatt seemed to have come on the national scene in 1944, when he joined Bill Monroe, fully formed as a musician and human being. Even his looks — somehow both homely and handsome, with a twist of a mouth and the eyes of a timeless mountain spirit — stayed much the same through the years. Scruggs, on the other hand, took a different road to remaining true to himself in changing times. His sons were deeply immersed in rock-era sounds, particularly those of Bob Dylan. Scruggs enjoyed picking around the house with his boys and the music they played together began to affect the duo's sound. Flatt and Scruggs albums such as 'Folk Songs Of Our Land' and 'Hard Traveling' had already started reflecting the music of the early '60s folk boom. As the decade moved on and producer Johnston took over supervision of the duo's albums, they came to contain songs by counterculture types such as Donovan, Pete Seeger and Buffy Ste. Marie, as well as a heaping helping of Dylan tunes. By almost all accounts, Flatt disliked the new direction. "I feel he didn't like the Dylan stuff," said Josh Graves, who played with the duo for 14 years and then worked with both men in their solo careers. "Some of it he liked and some of it he didn't like. But he did it anyway."

Flatt put it more bluntly to journalist Don Rhodes, whose extensive, revelatory 'Pickin'' magazine interview with Flatt came just months before the singer died on May 11, 1979. "Recording those Bob Dylan songs has as much to do with me wanting to quit doing records with Scruggs as anything," Flatt told Rhodes. (Personal and business differences also played a role in the breakup, as court filings showed through much of 1969. A settlement reached late that year ended the suits, but meant that neither could use the Foggy Mountain Boys name for his band.) Even though late-period Flatt and Scruggs albums such as 'Changing Times' and 'Nashville Airplane' consistently sold well, Flatt reportedly viewed the music as betrayal of their long-time fans. Scruggs has consistently declined chances to talk about past differences. But he agreed to talk about his longtime partner's contributions to music and entertainment. "We had the greatest association with each other and I thought he was one of the best showmen of all," Scruggs told me in September 1999, protesting that his words couldn't do justice to his feelings for Flatt. "He was a good singer and a good MC and he came off well on stage." The music included here shows a clear progression: from the last days of Flatt and Scruggs, through an experimental last fling with Columbia with Flatt as a soloist, through a return to a mainstream bluegrass sound on RCA and heralded collaborations with 1940s singing partners Mac Wiseman and Bill Monroe. (Flatt went on to record for a variety of labels, including Canaan, CMH and Flying Fish after leaving RCA in the mid-'70s.)

For the most part, the lamp of history has focused on the duo. That's understandable. The names Flatt and Scruggs still go together: like Abbott and Costello, like Lennon and McCartney, as basic a combo as bacon and eggs. "No one ever mentioned the word 'Lester;' no one ever mentioned Earl: It was always just Flatt and Scruggs," recalled Johnston, the producer who played such a controversial role in their careers. If one partner has been singled out, it has usually been Scruggs. (The esteemed 'Encyclopedia Of Southern Culture' has a separate entry for Scruggs, in which Flatt is mentioned.) That's understandable too. Scruggs has outlived his former partner by many years. And his contributions as an instrumentalist are more easily defined and traced than are Flatt's as a singer. The music on this set offers the first opportunity in many years for a full-fledged, separate look at Flatt as a person and a corresponding listen to him as a musician whose influence has been understated.

As a principal of the Nashville Bluegrass Band, Alan O'Bryant has been a key player in the revival of the kind of traditional bluegrass pioneered by Bill Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs. "I was a big fan of Lester's and always considered his singing to be the definitive version of a lot of the stuff that I heard: a lot of the bluegrass songs, a lot of the standards, even songs that I later found out that were covers," said O'Bryant, who first heard Flatt perform when O'Bryant was a North Carolina teenager in the early '70s. "And starting out, that was some of my first impression of how people were supposed to act when they were on stage. Lester was real comfortable and had a way of winning people over that wasn't too formal. I think that general attitude pervades our presentation until today."

As the millennium closed, there were plenty of people around who played roles in Flatt's life in the years 1966 until 1974, when he sang and played on the recordings in this set. In separate interviews with Flatt's friends and associates, a picture emerged of the singer in the late '60s and early '70s as genial, often full of fun, devoted to music and confident in his professionalism. After his decades of stardom, Flatt never got "above his raisin'," even in the jobs he agreed to play. "We did some drive-in theaters when I was with Lester," Vic Jordan said. "You'd play on top of the concessions stand. You'd have a couple of microphones and they'd pipe the sound right into the speakers in people's cars. Instead of applauding, the people'd blow their horns. That was an experience I never had with anyone else."

Lester Flatt Flatt On Victor Plus More (6-CD)

Read more at: https://www.bear-family.com/flatt-lester-flatt-on-victor-plus-more-6-cd.html

Copyright © Bear Family Records

Copyright © Bear Family Records®. Copying, also of extracts, or any other form of reproduction, including the adaptation into electronic data bases and copying onto any data mediums, in English or in any other language is permissible only and exclusively with the written consent of Bear Family Records® GmbH.

More information about Lester Flatt & Bill Monroe on Wikipedia.org

Ready to ship today, delivery time** appr. 1-3 workdays