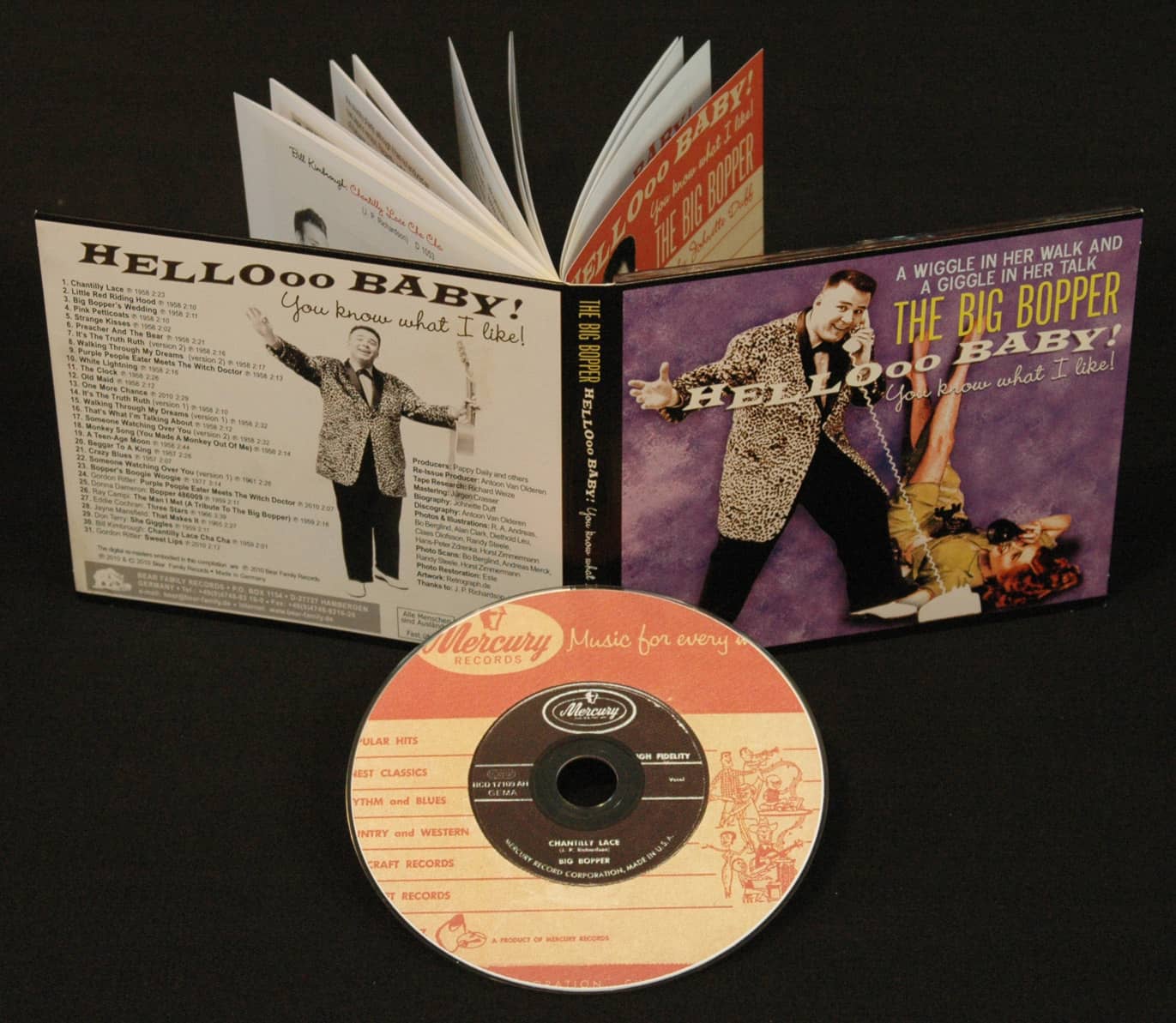

Who was/is Big Bopper ? - CDs, Vinyl LPs, DVD and more

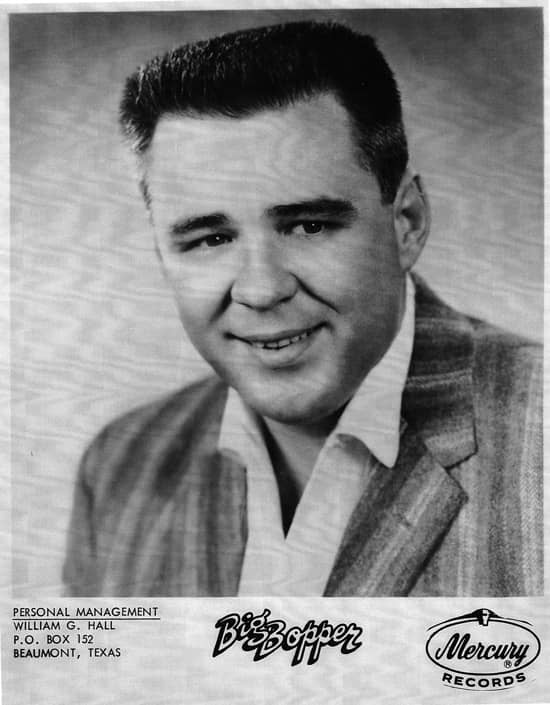

Big Bopper

Hello Baby - You know what I like!

February 2, 1959

J iles Perry Richardson, Jr., known to his legions of fans as the Big Bopper, finished his last set at Clear Lake, Iowa's Surf Ballroom and changed into a red flannel shirt and light blue pants. He checked the time on his watch, a gift from his former boss, Jack Neil, back at KTRM radio in Beaumont, Texas. He found a bottle of Bufferin in his briefcase and swallowed a couple of tablets – he was fighting a nasty cold, made even worse by the horrible winter weather in the Midwest in the winter of 1959.

iles Perry Richardson, Jr., known to his legions of fans as the Big Bopper, finished his last set at Clear Lake, Iowa's Surf Ballroom and changed into a red flannel shirt and light blue pants. He checked the time on his watch, a gift from his former boss, Jack Neil, back at KTRM radio in Beaumont, Texas. He found a bottle of Bufferin in his briefcase and swallowed a couple of tablets – he was fighting a nasty cold, made even worse by the horrible winter weather in the Midwest in the winter of 1959.

The lack of heat on the tour bus hadn't helped. Jape, his nickname to family and friends, remembered a family picture with his two brothers, taken when he was ten during a rare snowfall on the Texas Gulf Coast where he grew up. He stood in the middle of the siblings, his arms around his younger brothers, sticking out his tongue to catch the snowflakes. Snow might be fun when you were a kid, but it meant nightmare conditions for the musicians on the Winter Dance Party tour. What were the tour promoters thinking?

Jape knew that Buddy Holly, the most established headliner on the tour, had chartered a plane over at the Mason City, Iowa, airport for himself and a couple of members of his band to reach the next stop in Fargo, North Dakota, under better circumstances than they had been experiencing. Goose (Carl Bunch, Buddy's drummer) wasn't going – that was for damn sure – 'cause he was in the hospital with frostbitten toes. For once, not only had the heater given out but so had the bus. Stalled out in the middle of nowhere.

Only the fortuitous intervention of local law enforcement saved them all from death by hypothermia. Risking his life hadn't been part of his contract. Even burning newspapers in the aisle of the old school bus didn't seem likely to rescue them from the ever-decreasing temperature before the flashing lights showed up.

Jape decided he was going to work on Waylon Jennings, Buddy's bass player, or better yet challenge him to another game of craps and see if they could strike a deal for Jape to go in his place. Tommy Allsup and Waylon, a fellow Texan like Jape and Buddy, were currently the other two passengers lined up for the three-passenger plane.

Jape knew that Dion, a New Yorker a little more accustomed to cold winter weather, couldn't believe that Buddy was asking his backup musicians to fork over $36 for the plane ride. Dion's parents paid $36 a month for rent back home – it wasn't worth it. But Jape also knew performing was going to become impossible if he didn't get to a doctor and he needed to keep singing to send the money back home to his 'babies' – his pregnant wife Teatsy and their five-year-old daughter Debbie.

And there would be the added benefit of time to actually do laundry, a luxury that only extra time could buy. The stench on the bus was unbelievable – and, although they had missed their gig the night before because of the bus breakdown, there was rarely time to get to their next stop and set up for the performance on the schedule, much less time for anything else.

While the tour bus zigzagged across the Midwest in an inefficient pattern unfathomable to the musicians (from Wisconsin to Minnesota to Iowa back to Minnesota, then back to Wisconsin, then Iowa again!), Jape spent countless dark and cold hours on the bouncing tour bus, which was really just an old school bus, writing into the notebooks he carried everywhere. Bits of song lyrics, snatches of melody, visionary ideas for the music business – Jape always made sure he wrote his ideas down.

Waylon couldn't help but ask what he was always scribbling.

"Right now, I'm writing a song for my son," Jape told him.

"How old is he?" Waylon asked.

Teatsy was due in April, Jape explained. He told Waylon how much he missed his wife and daughter, who were staying in Louisiana with one of her sisters awaiting the birth of their second child. Jape sent Teatsy and Debbie postcards and letters as frequently as he could find time, stationery and stamps, often beginning his messages with, "Hello, babies!"

"How do you know it's a boy?” Waylon asked.

Jape just smiled. He knew.

Waylon and Jape had a lot in common and Jape had bonded with the 17-year-old wunderkind from California, Ritchie Valens, bound as they all were by the miserable conditions. The boy clearly had talent, had hit it big with Donna and La Bamba. Ritchie had shown up in Chicago for the start of the tour in his shirt-sleeves, though, having little idea what was in store for him.

Waylon and Jape had a lot in common and Jape had bonded with the 17-year-old wunderkind from California, Ritchie Valens, bound as they all were by the miserable conditions. The boy clearly had talent, had hit it big with Donna and La Bamba. Ritchie had shown up in Chicago for the start of the tour in his shirt-sleeves, though, having little idea what was in store for him.

Ritchie vowed to go back to California after the bus broke down, the seemingly final straw, and even obtained the blessing of his manager to abandon the ill-conceived tour. But his mother shipped off a winter coat and the package finally caught up with the guys just days before. In honored show biz tradition, Ritchie decided the show must go on, even though he had never been so cold.

Jape wasn't sure the new coat was as warm as the sleeping bag he zipped himself up in to sleep on the bus, but he was glad Ritchie hadn't abandoned them. And so it was that Ritchie challenged Tommy Allsup to a coin toss for his seat on the plane and Jape went in search of Waylon Jennings to beat him at yet another game of craps. Waylon told the story years later, his survivor's guilt still intact. Buddy wasn't happy that his band wasn't going with him and that his bass player was relinquishing his seat.

"Well, I hope that old bus freezes up on you again," Waylon said Buddy told him. "Yeah, well, I hope your ole' plane crashes," Waylon responded. Waylon climbed on the bus with Dion and the Belmonts and Tommy Allsup and the other musicians from the tour as Carroll Anderson, the manager, turned out the lights of the Surf Ballroom.

Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper joined Buddy Holly in Anderson's car, for he graciously offered to drive them over to Mason City, Iowa, to catch the chartered plane. Anderson knew Bopper's wife was pregnant because Jape made a point of asking Bob Hale, emcee at the Surf, if he could touch his pregnant wife's belly – the Big Bopper was clearly sick as well as homesick, missing his own wife and little girl and anxious for the birth of his second child.

Anderson and the musicians reached the airport shortly before midnight. Jerry Dwyer, of Dwyer Flying Service, was there, along with his young pilot, Roger Peterson. Reluctantly, Jape handed over $36 in cash and Dwyer wrote out a receipt. Jape reminded himself the plane wasn't a luxury – it was a necessity if he was going to keep going – but he also remembered his $85 bank balance back home. Dwyer made the receipt out to J. P. Richardson and dated it 2-2-59. The musicians thanked Anderson and sought the shelter of the small plane against the weather while Peterson tinkered with the controls.

Anderson and the musicians reached the airport shortly before midnight. Jerry Dwyer, of Dwyer Flying Service, was there, along with his young pilot, Roger Peterson. Reluctantly, Jape handed over $36 in cash and Dwyer wrote out a receipt. Jape reminded himself the plane wasn't a luxury – it was a necessity if he was going to keep going – but he also remembered his $85 bank balance back home. Dwyer made the receipt out to J. P. Richardson and dated it 2-2-59. The musicians thanked Anderson and sought the shelter of the small plane against the weather while Peterson tinkered with the controls.

Shortly after midnight, the plane took off. Dwyer was never able to make contact with Peterson after he lost sight of the plane in the dark landscape. It was February 3, 1959, by now, the night before the dawning of 'The Day The Music Died' in a snow-covered Iowa cornfield.

One of the oft-repeated myths that sprung up after the success of Don McLean's ode to that day was that the plane the musicians boarded was named 'American Pie.' The call letters of the Beechcraft Bonanza were N3794N – but it had no name. That was not the only myth that would be passed down about that day and the musicians who died.

BIG BOPPER Hello Baby - You Know What I Like

Read more at: https://www.bear-family.com/big-bopper-hello-baby-you-know-what-i-like.html

Copyright © Bear Family Records

Copyright © Bear Family Records®. Copying, also of extracts, or any other form of reproduction, including the adaptation into electronic data bases and copying onto any data mediums, in English or in any other language is permissible only and exclusively with the written consent of Bear Family Records® GmbH.